As she described it:

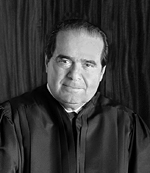

Here we have a perfect example of what’s so very wrong about so-called originalism, the theory Scalia claims to follow. The idea is that the Constitution should be interpreted according to its authors’ original intent, no changes allowed.(emphasis added). While some self-professed "originalists" subscribe to this theory, Justice Scalia is unquestionably not one of them.

In his book, A Matter of Interpretation

Government by unexpressed intent is . . . tyrannical. It is the law that governs, not the intent of the lawgiver . . . . Men may intend what they will; but it is only the laws that they enact which bind us.(P. 17). Lest you think Scalia feels differently when interpreting the Constitution as opposed to statutes:

It is curious that most of those who insist that the drafter's intent gives meaning to a statute reject the drafter's intent as the criterion for interpretation of the Constitution. I reject it for both.(P.38). So what's the bottom line:

What I look for in the Constitution is precisely what I look for in a statute: the original meaning of the text, not what the original draftsmen intended.(P. 38). I think that's a pretty concise explanation of the difference between Scalia's originalism and intent-based originalism. Scalia's main essay in A Matter of Interpretation is only 45 pages. I highly recommend it for anyone interested in this subject. His book also includes comments and criticism from leading scholars (Amy Gutmann, Gordon Wood, Laurence Tribe, Mary Ann Glendon, and Ronald Dworkin). For a different take, Justice Breyer published his own book addressing interpretation, Active Liberty

Posted by Philip Miles, an attorney with McQuaide Blasko in State College, Pennsylvania in the firm's civil litigation and labor and employment law practice groups.

No comments:

Post a Comment